Introduction

Anxiety is a normal part of our daily lives. However, many people experience chronic or severe anxiety to the point where it interferes with their functioning. In our society today, billions of dollars are spent each year helping people alleviate their anxiety symptoms.

What is Anxiety?

Anxiety is our body’s natural stress response. It includes feelings of nervousness, worry, and fear along with bodily changes that accompany such feeling, like increased heart rate, feeling flushed, sweating, etc. Anxiety also includes thoughts and behaviours that we have before, during, and after an anxious response.

Bidirectional Model of Anxiety

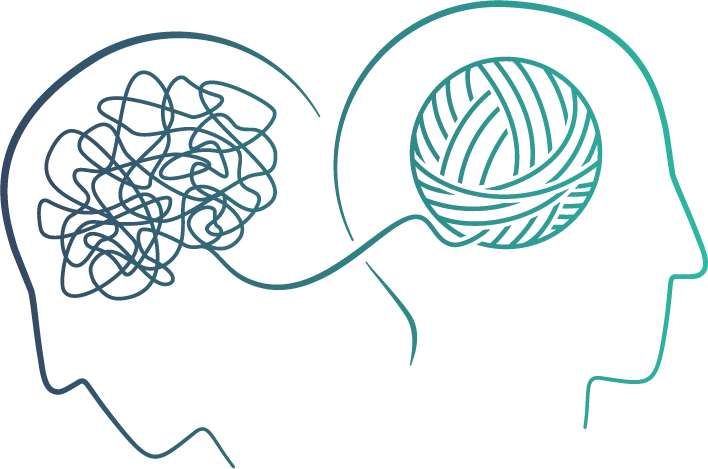

Research on anxiety breaks it down into bidirectional relationships between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (see diagram below). That is, our thoughts influence our feelings and sensations, which in turn affect our behaviour. The way we behave can then influence our thoughts and feelings. When anxiety becomes out of control, anxious thoughts and avoidance behaviours may create more or unnecessary feelings of anxiety.

Anxiety Can Be Helpful

While anxiety may feel unpleasant, it can actually be adaptive and potentially life-saving. For example, if we didn’t have anxiety, we might not prepare for a job interview, look both ways before crossing the street, or avoid a potentially angry bear while camping.

Anxiety and the Stress Response

Anxiety is associated with our “fight-flight-freeze” stress response. That is, in a potentially dangerous situation, our body undergoes a series of chemical and physical changes to protect us. Ultimately, we either “freeze” in place, “flee” the situation, or “fight” the danger head-on.

When Anxiety is Not Adaptive

Sometimes anxiety can grow to the point where it is no longer helpful. For example, we may become so paralyzed with anxiety that we “blank out” on a test even though we studied. Anxiety may also prevent us from meeting new people at a party and fostering friendships. During these situations, we may experience inaccurate or unhelpful thoughts that actually perpetuate our feeling of anxiety.

In order to determine if your anxiety is growing out of control, consider if your level of anxiety is disproportionate to the stressor causing the anxiety and the degree of impairment it has. For instance, do you feel anticipatory anxiety for weeks prior to having a relatively small job evaluation? Does this anxiety prevent you from going to work or impair your productivity? As another example, have you actually run into a bear while camping, or do you just feel anxious in the absence of danger?

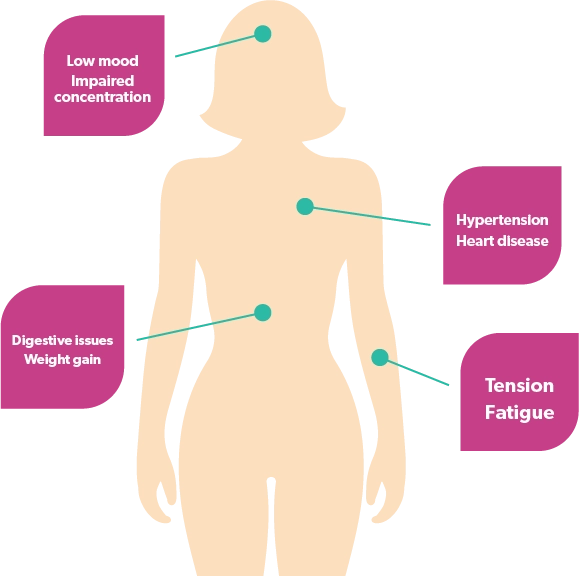

Long Term Effects of Anxiety on the Body

Over time, anxiety causes your brain to emit stress hormones on an ongoing basis. This can lead to a number of physical, mental health, and cognitive issues, such as low mood, headaches, muscle tension, fatigue, dizziness, digestive issues, weight gain, impaired concentration, and forgetfulness. You also may be more susceptible to hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and colds/flus (due to stress-induced compromised immune system).

Anxiety Triggers

There is a myriad of potential anxiety triggers. Common ones include caffeine, changes in blood sugar from skipping meals, money, social interaction, interpersonal conflict, heights, spiders, public speaking, major life changes (e.g., new job, wedding), social/cultural/environmental crises, and trauma. It can also be triggered by smaller situations rather than major catastrophic events, such as deciding where to go for vacation or planning a birthday party. Anxiety can further be triggered by internal stressors, such as negative thoughts, people pleasing tendencies, perfectionism, and a fear of failure.

Worry

Worry is a special category of anxiety that also involves our thoughts, emotions and behaviours. However, it is best described as “scenario building” in our minds. Typically, worry involves thinking about potentially negative events or situations in the future, often the “worst case scenario”. These thoughts are usually based on little factual evidence. Some of us worry more than others. In more severe cases, worry influences our concentration, reasoning, and ability to regulate our emotions.

Worrying is typically associated with bodily symptoms such as muscle tension, headaches, restlessness, increased heart rate, shallow breathing, and fatigue. It can also look like irritability, sleep difficulties, and indecisiveness. People who worry may engage in behaviours such as:

- Over-researching or over-checking plans, schedules, instructions, etc.

- Reassurance seeking from loved ones

- Difficulty letting others take control of a situation

- Perfectionism

- Procrastination

Worrying requires solutions. However, uncontrollable worry often hinders our problem-solving abilities. Unfortunately, in the moment, we sometimes are not aware that our problem-solving abilities are being affected. Indeed, worrying gives us something to do, so we may feel closer to an actual solution, when in fact this may not be the case.

*It is important to keep in mind that worrying does not prevent unpleasant or negative things from occurring, but prevents you from being aware of the positive emotions and experiences in life.

Anxiety at Night

Many individuals experience a worsening of anxiety symptoms in the evening (e.g., while in bed). For instance, they may have difficulty “shutting their brains off” and feelings of restlessness leading to challenging falling or staying asleep. During the day, some individuals may feel like their anxiety is manageable, as they are able to stay busy and distract themselves. However, in bed, we usually are drained of emotional energy required to fight off rumination and worry. We are less distracted during this time as well. In this situation, our bodies are fighting our natural circadian rhythm (i.e., when the sun goes down, melatonin increases in our body, which tells us to rest).

Panic Attacks

Panic attacks are seemingly spontaneously periods of intense, overwhelming anxiety or fear. They are often accompanied by bodily symptoms such as feeling faint, chills or hot flashes, shortness of breath, numbness, or racing heart. Sometimes individuals will think they are having a heart attack due to the nature and severity of their panic attack symptoms. While they may be distressing, they cannot hurt you.

Panic attacks are problematic when they occur often. Many people then become worried about having another one, and may avoid certain people or places as a result.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety typically comes and goes. However, if it lasts for extended periods of time (usually a number of months) and interferes with your life, it may develop into an anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders can affect any age and population; however, women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (Pearson et al., 2013).

Causes of Anxiety Disorders

Typically, anxiety disorders are caused by a combination of factors, including a genetic predisposition, changes in brain chemistry, and environmental stressors.

Risk Factors

There are a number of risk factors identified in the research to be related to the development of anxiety disorders. For instance, several factors include certain physical illnesses/conditions (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome), ongoing stress, family history, childhood development issues, and a history of other mental health issues (e.g., depression, substance abuse, trauma, another anxiety disorder).

Types of Anxiety Disorders

There are several types of anxiety disorders. The most common include:

- Specific Phobia

- Panic Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Social Anxiety Disorder

- Selective Mutism

- Separation Anxiety Disorder

Specific Phobias are fears beyond the usual reaction to a particular object or situation. In many cases, these objects or situations are avoided. There are five subtypes of specific phobia:

- animal type (e.g., spiders)

- natural environment type (e.g., fear of heights)

- blood/injection/injury type (e.g., fear of seeing blood)

- situational type (e.g., fear of enclosed spaces)

- other type (e.g., fear of choking)

Involves recurrent spontaneous panic attacks followed by ongoing worry about having another one and engaging in subsequent avoidance behaviours.

Agoraphobia involves significant anxiety related to various public situations, such as using public transportation, being in open or enclosed spaces, being in a crowd, and being outside of the house. These situations are often avoided and generate extreme amounts of anxiety due to irrational thoughts that escape may be difficult or that help may not be available.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder involves excessive anxiety and worry on an ongoing basis that is difficult to control. It is often associated with symptoms such as feelings of restlessness, fatigue, irritability, concentration difficulties, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. Further, the anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause significant impairment in one’s daily functioning.

Social Anxiety Disorder goes beyond mere “shyness”. It described significant anxiety in social situations and fear of being negatively evaluated by others. This fear is disproportionate to the actual or perceived threat posed by the social situation. As such, social situations are often avoided.

Selective Mutism and Separation Anxiety Disorder can occur at any age, but are most prevalent in children. Selective Mutism involves a failure to speak in social or public situations due to severe anxiety, which causes impairment in school or home functioning. Separation Anxiety Disorder involves a developmentally inappropriate and excessive fear of being separated from parents, partners, or other attachment figures.

Separation Anxiety Disorder involves a developmentally inappropriate and excessive fear of being separated from parents, partners, or other attachment figures.

Treatment of Anxiety

In mild-to-moderate cases, lifestyle changes and cognitive-behavioural coping strategies can be used to effectively address anxiety symptoms. These strategies can be implemented on your own, or with assistance from a trained mental health professional. In moderate-to-severe cases, cognitive behavioural psychotherapy and/or medication may be helpful.

Medication

Medication treats anxiety by balancing brain chemistry, preventing the onset of anxiety symptoms. The main medications used to treat anxiety are Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s), Norepinephrine and Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (NSRI’s) and Benzodiazepines. SSRI’s and NSRI’s are considered “antidepressants” and are commonly prescribed to treat both anxiety and depression. Benzodiazepines are “sedatives” that are used to treat anxiety or insomnia. However, treatment outcomes are optimized with a combination of medication and psychotherapy.

Lifestyle Changes

There are many lifestyle changes that you can try to address anxiety symptoms. These may include the following, which serve to deactivate the “fight-flight-freeze” stress response:

- Meditation/yoga

- Deep breathing

- Exercise

- Warm bath

- Essential oils

- Weighted blanket

- Playing with pets

- Spending time with loved ones

- Reading

- Creating art

- Listening to music/nature sounds

- Getting adequate sleep

- Eating healthy

- Avoiding caffeine and alcohol

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behaviour psychotherapy is the gold standard for addressing anxiety symptoms. It teaches you ways of challenging unrealistic thoughts that provoke anxiety symptoms and how to calm the body. It also teaches you strategies to stop engaging in rumination and maladaptive avoidance behaviours. For instance, psychotherapy can also teach you how to tolerate uncertainty.

Tolerating Uncertainty

Uncertainty is unavoidable in life. People who struggle with uncertainty are more likely to feel anxious. As a result, they may engage in reassurance seeking, over-checking, and procrastination, and may have problems delegating tasks. In contrast, people who are able to tolerate uncertainty are less likely to experience anxiety symptoms.

To do this, we can shift our behaviour to become more tolerant of uncertainty in two ways: increasing exposure to uncertain situations and decreasing behaviours that reduce uncertainty. Changing our behaviour directly influences our feelings and thoughts.

- For instance, we can ask ourselves questions to challenge anxious thoughts, such as:

- What could I do to cope if the worst-case scenario did happen?

- What are at least three other possible outcomes?

- What is the most likely case scenario?

- What can I do about this right now?

- If the feared outcome does occur, how will I feel about this in two years? Ten years?

To answer these questions, other than being honest with yourself, you can look for evidence to support these anxious thoughts.

Calming the Body

Turning off the “fight-flight-freeze” response can be done in a number of ways. Here are some of the most common and effective.

Babies naturally engage in diaphragmatic breathing; you can see their stomachs rise and fall with each breath. As we age, our breathing becomes more shallow (i.e., chest breathing). When we feel anxious, we also tend to take shorter and more shallow breaths that can lead to hyperventilation. When you mindfully switch to diaphragmatic breathing, it stimulates a part of our nervous system involves in the relaxation response.

To do this, rest your hand on your stomach and feel it rise and fall as you breathe. Breathe in deeply for a count of four, expanding your diaphragm. Your hand should rise. Slowly release your breath for a count of four. You should feel your hand lower.

Guided imagery is a great way to relax. The most effective imagery engages as many of your senses as possible. Taking yourself somewhere safe and pleasant in your mind can be helpful for improving anxiety and mood symptoms. While you can practice this on your own, you can also listen to videos, podcasts, and audiobooks that help to guide you on this journey.

Progressive muscle relaxation is a technique that moves through each of our body’s major muscle groups to relieve anxiety-related tension. This involves systematically and slowly tensing and relaxing each muscle, one at a time, for ten counts each. It is based on the premise that we cannot be relaxed and stressed/anxious at the same time.

Exposure

Psychotherapy often involves gradual exposure; once you learn how to calm the body, you are gradually exposed (either directly or through your imagination) to your feared situation that triggers anxiety. For instance, if you have a fear of dogs, you will be asked to spend time with dogs. As many people find it very difficult to face their fears, you will be asked to start with situations that create only mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety, and then gradually progress to situations that create severe anxiety. For instance, in treating a fear of dogs, you may first be asked to look at photos of dogs, until you eventually are able to pet various breeds of dogs.

Special Considerations: Anxiety in Children and Adolescents

Anxiety in youth is very common. In fact, a survey of over 11,000 Ontario students in grades 7 through 12 from 2017 demonstrated that close to 40% reported at least moderate anxiety and depression symptoms. In addition, rates of anxiety have dramatically increased in comparison to prior surveys in 2015 and 2013.

If youth present with ongoing anxiety that is chronic and debilitating in nature, it should be addressed in a timely manner.

Anxiety may present differently in children and adolescents in comparison to adults. Common signs and symptoms of anxiety in youth include:

- Feelings of nervousness and/or panic

- Tearfulness

- Nightmares

- Tantrums

- Jitteriness

- Irritability

- Sleeplessness

- Avoidance of certain people or places, such as school or social interaction

- Separation anxiety

- Physical complaints (e.g., fatigue, stomach aches, muscle tension, headaches)

- “Acting out” in school or at home

- Substance abuse

- Changes in appetite

Similar to adults, lifestyle changes and cognitive behavioural coping strategies can be effective in managing anxiety in youth. Psychotherapy is also a great way to teach youth about effective coping skills for anxiety management. For older youth, psychotherapy combined with medication may be considered.

How to Support a Loved One with Anxiety

Here are some basic strategies for supporting a loved one with anxiety:

- Avoid using the phrases “calm down” or “just relax”

- Learn as much as you can about anxiety symptoms and treatment

- Encourage them to develop and follow a treatment plan outlined by a health professional

- Encourage ongoing communication

- Validate them and be supportive, without supporting maladaptive coping strategies such as reassurance seeking or avoidance behaviours

- Remember that progress is made in small steps

- Model healthy coping strategies for anxiety management

Conclusion

In summary, anxiety is an important part of our lives, and sometimes can be adaptive. However, chronic anxiety that interferes with your daily functioning should be addressed in a timely manner so it does not become worse. Importantly, there are many evidence-based strategies available that can reduce and eliminate your anxiety symptoms.

Are you one of the many people that experience anxiety on a regular basis? What strategies do you find helpful to cope?