Introduction

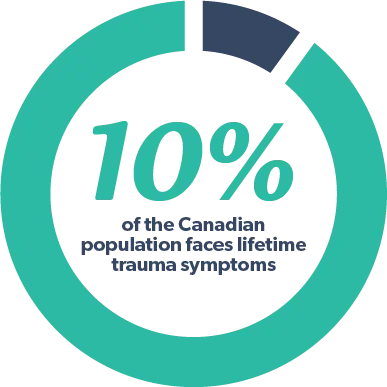

Canada has one of the highest prevalence of lifetime trauma symptoms, affecting close to 10% of the population (Duckers et al., 2016).

What is Trauma?

Trauma is the emotional response when an injury or event overwhelms us and causes a great deal of distress. It is often unexpected and tends to involve feelings of powerlessness or helplessness. One traumatic event identified by one person may not be described as such by another. However, common trauma events include the unexpected death of a loved one, sexual assault, childhood neglect, natural disasters, accidents, and being witness to a death or injury. Traumatic injuries and events can occur once or repeatedly.

How Does Trauma Affect People?

Trauma can affect anyone, at any age. Trauma can change our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. It also has the potential to affect our concentration, relationships, work performance, and daily functioning. For example, trauma can change the way you feel, by eliciting too much or too little emotion. It may prompt depression, anger, or anxiety.

As another example, trauma can change how you view the world. For instance, you may develop a distrust of others or view the world as unsafe or corrupt.

Further, trauma can change your physical health and daily functioning. For instance, you may avoid places, people, or objects that remind you of the trauma; you may have nightmares or disrupted sleep; or you may have difficulty leaving the house. Similarly, you may notice changes in appetite or bodily complaints (e.g., fatigue, muscle tension, headaches, digestive problems).

How we respond to, and cope with, trauma depends on age, the severity and frequency of the injury/event, and whether it occurred directly or indirectly (i.e., happened to you, happened to someone else, or heard about it).

While the above-mentioned symptoms are normal and usually resolve over time, sometimes individuals experience trauma-related difficulties over extended periods of time (i.e., months) on a regular basis, to the point where it impairs their daily functioning. In these cases, our internal “alarm” becomes activated in the absence of actual danger. As such, we try to suppress this warning to the best of our ability, often using unhealthy strategies such as acting out aggressively, scanning our environment, avoiding people/places, or abusing substances. While there may be temporary relief, this does not alleviate our trauma symptom on a long-term basis.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Although symptoms of trauma and posttraumatic stress have been well-documented over the last hundred years, its label has changed over time. Following both World Wars, such symptoms were collectively referred to first as “shell shock”, followed by “combat fatigue” and “war neurosis”. Most recently, it has been referred to as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition).

PTSD Symptoms

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder causes intrusive symptoms such as flashbacks of the traumatic event, nightmares, or memories of the event that seem to come from nowhere. Individuals subsequently tend to avoid people, places, and objects that may trigger intrusive symptoms. Many people also experience negative changes to their mood, behaviour, and thoughts, such as irritability, guilt, concentration difficulties, numbness, feeling “jumpy”, feeling disconnected from their body, or having an increased state of alertness. Notably, symptoms may not always appear immediately following the traumatic event.

Commonly, individuals also experience other mental health issues in addition to their PTSD symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, suicidality, and/or substance abuse.

Causes

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder is caused by a combination of factors, including genetic predisposition, prior life experiences, history of trauma, chemical changes in the brain, and temperament.

Risk Factors

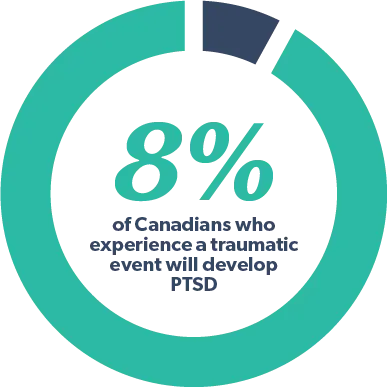

While most individuals experience trauma at some point, not all of these experiences result in the development of PTSD. About 8% of Canadians who experience a traumatic event will develop PTSD (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2013). Factors that increase one’s risk of developing PTSD include pre-existing mental health issues, the length of time the trauma lasted, the number of prior traumatic events, one’s reaction to the event, and degree of support following the event. Military personnel, first responders, and medical professional are at higher risk of developing PTSD. Similarly, individuals who suffer from social, economic, or educational disadvantage are more likely to develop PTSD. Though men tend to experience traumatic events more frequently than women, women are more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Tolin & Foa, 2006).

Protective Factors

Protective factors that may decrease one’s risk of developing PTSD include adequate social support, seeking therapeutic intervention after the event, having adequate coping strategies for dealing with stress/trauma, and being able to act effectively/efficiently in traumatic situations despite feelings of fear or anxiety.

Treatment

Treatment for PTSD often includes both medication and trauma-focused psychotherapy. In terms of medication, some specific SSRI’s (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) and SNRI’s (Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors) used for depression and anxiety also work for PTSD.

Trauma-Focused Psychotherapy

Trauma-focused psychotherapy comes in many forms. Most commonly, research suggests that trauma-focused psychotherapy utilizing a cognitive behavioural framework results in the effective treatment of PTSD. This type of psychotherapy can be done individually or in a group format. Specifically, it provides education about your body’s response to trauma and teaches you strategies for managing trauma symptoms (e.g., calming the body and mind when triggered). It also focuses on challenging negative thoughts brought on by trauma. Another important component includes prolonged exposure techniques (i.e., talking about your trauma repeatedly in a safe therapeutic environment until your memories are no longer upsetting). Prolonged exposure also involves addressing avoidance behaviours due to trauma symptoms (i.e., going places that are safe but previously avoided as they reminded you of the trauma).

Triphasic Model

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy also utilizes the Triphasic Model of Trauma. It states that trauma recovery can be addressed in three stages:

- Safety and Stabilization: determining what areas of life require stabilization and implementing a plan for this (e.g., learning how to regulate emotions or feel safe in relationships).

- Remembrance and Mourning: processing trauma in a way that does not involve an escalation of emotions and exploring the losses associated with the trauma.

- Reconnection and Integration: taking steps towards empowerment and recovery.

Other Coping Strategies

Mindfulness is another effective coping strategy for addressing trauma symptoms, which includes bringing focused, non-judgemental awareness to our thoughts and emotions. Over time, mindfulness practice can increase emotional regulation and bodily awareness. Similarly, spending time in nature and building a support system can also be beneficial. Many individuals opt to have a “therapy pet” that allows them to manage their trauma symptoms, particularly in the community.

Anniversary Date

People can have various trauma triggers. However, a common trigger is the anniversary date of the traumatic event. During this time, trauma symptoms often become worse. To feel better, some individuals give back to their community, visit a grave, find ways of commemorating individuals involved, or spend time with family.

Trauma in Children

Trauma can affect children and adolescents in different ways. For instance, children in elementary school may have separation anxiety, sleep difficulties, digestive issues, temper tantrums, nightmares, school avoidance, or social withdrawal. They may fall behind in school or act out the trauma through play, drawings, or stories. They may also avoid people, places or objects that remind them of the trauma. Sometimes, they may not remember all details involved in the traumatic event. In addition, they may experience regression in their behaviours (e.g., returning to thumb sucking or wetting the bed).

Adolescents may have trauma symptoms that are more similar to adults, such as changes in mood, anxiety, sleep difficulties, anger/aggression, impulsivity, concentration difficulties, self-harm, intrusive memories/thoughts of the trauma, or substance abuse. They also experience avoidance behaviours and changes in mood and thoughts associated with the event.

Sometimes, children and adolescents hesitate to disclose the trauma to parents or other trusted adults initially. They may require time and/or gentle prompting to do so. In the meantime, parents and caregivers have to make sense of the changes they notice in their child’s behaviour, mood, and play.

Youth who have experienced trauma require solid social support and increased time with their parent or caregivers following the event. They perform best in a structured and predicable environment with many activities that can provide distraction. Bedtime routines and proper sleep hygiene are important as well. Parents and caregivers can listen and validate the child’s experiences; they can also encourage the child to gradually address any avoidance behaviours. Parents and caregivers can also model appropriate coping strategies for dealing with large emotions and calming the body when escalated. Lastly, trauma-focused psychotherapy and/or medication may be warranted depending on the child’s age and severity of symptoms.

Conclusion

The definition of “getting better” varies for different people. It is important to know that there are many treatment options for trauma and PTSD. For many, these interventions alleviate symptoms completely, while for others, they find that their symptoms are less intense or are reduced. Ultimately, your trauma symptoms don’t have to interfere with your everyday life.

How can you support yourself or a loved one who has experienced a distressing event? How can you provide support both immediately and in the long-term?